Documentary (DOC) 150: Introduction to Documentary Storymaking is the first course in the five-course consortial LVAIC Documentary Minor. In the Fall 2018 section of the course, 16 students enrolled from the three institutions in the consortium: Muhlenberg College, Lehigh University, and Lafayette College.

The students ranged from sophomores to seniors. Some were serious students of media production with plans to complete the Minor in Documentary Storymaking, while others are housed in distant disciplines and are hoping for a fun, (maybe easy) creative elective.

I designed DOC 150 to build on my interests in decolonizing documentary practices and on an earlier community-based documentary production class designed by Aggie, which included a partnership with Allentown nonprofit, Pennsylvanians Organized to Witness, Empower, and Rebuild (POWER) Lehigh Valley (then POWER Northeast).

This year, I partnered DOC 150 with community nonprofit, the Allentown Coalition for Economic Dignity (ACED), a subcommittee of POWER Lehigh Valley. A storytelling partnership with DOC 150 was a mission-fit for ACED. As an organization of researchers, organizers, and educators, ACED aims to ensure that the steps taken to address community development are representative of community desires. ACED does this by creating opportunities for community dialogue, soliciting community input, and delivering that input to city officials to push for strategies and solutions that will serve the community and will address rather than exacerbate racial and economic inequities (ACED, n.d.).

The course’s partnership with ACED was made stronger through the support of a Mellon Community Engagement grant from Muhlenberg College, which allowed for the hiring of a teaching assistant, Drew Swedberg, and classroom support from Assessment and Outreach Librarian at Muhlenberg College, Jess Denke. Jess and Drew are also lead organizers of ACED and thus served as powerful bridges between community and classroom.

Over the course of the semester, DOC 150 became a space through which students could enact documentary principles toward supporting ACED’s work to lift up community voices and inform policy decisions. Students dove into this work with great enthusiasm, even though half the class lived as far away as Easton. We started the semester studying critical pedagogy, documentary histories, documentary authority, and documentary risks. We discussed the differences between a charity and justice framework and analyzed the differences between storytelling that reinforces the myth of the individual and storytelling that instead draws our attention to systems and structures that shape the individual. We guided students in thinking about their own “location” (Coles, 1997) relative to the issues and to the communities with which they would be engaging.

Their first assignments asked students to document each other to practice listening, interviewing, and making story selections. We watched these short, edited profiles as a class so that students could experience and reflect upon how it feels to have one’s story in someone else’s hands and available to the public. Next, students worked in small teams to produce short profiles of a person, organization, or issue that demonstrated the ways in which issues of development were intersecting with their own lives. For example, students made pieces about a nonprofit at which they had volunteered and about the ways that their own universities were gobbling up neighborhoods in expansion efforts. In this way, we were hoping to disrupt the facile documentary impulse to “make a film on/about the ‘others’” (Minh-ha, 1991, p. 60) and, instead, to foster in students a sense of themselves as cohabitants of the same ecosystem with regards to the issues even if affected by the issues differentially.

With a foundation in questions of vulnerability and responsibility, we moved into studying those specific issues facing Allentown’s urban core. In addition to readings, screenings, and conversations with community representatives, students engaged with the issues by way of a video editing exercise. The class’s teaching assistant, Drew, had shot several interviews with community members and organizers in Allentown reflecting on how the City’s development efforts were affecting long-term residents. Students were tasked with editing together interviews with visual material (what is customarily called “BRoll”) into a two to three minute short video that could have a beginning, middle, and end; engage audiences with the issues; and add to the dialogue without reinforcing myths or stereotypes. Students worked in small groups of two or three, each team editing from the same collection of recorded video material. We watched all the edits as a class to understand how the same video can be shaped differently in different hands. Drew and I then selected one version that most successfully met the project criteria to open a public forum hosted by ACED at the public library.

Acclimating to the issues and community perspectives by way of pre-existing / already-shot video material allowed us to work out some of the student’s questions or confusions in the safe space of the classroom, before entering into the community. In editing these interviews, students inquired into the highest priorities for ACED, data and informational contexts for further framing the issues, and relationships between images, interviews, narrative structure, and audience. In one conversation, for example, we wondered what information to include in the videos if the primary audience for the short films were City officials versus community members, two constituencies with different needs and perspectives. Due to the inquiry-based model of classroom discussions and the diligence with which students worked, the winning video that screened at the ACED public event was inspiring and generated robust community dialogue. This helped to reinforce our relationship with ACED, securing their confidence in the students’ thoughtfulness and sensitivity.

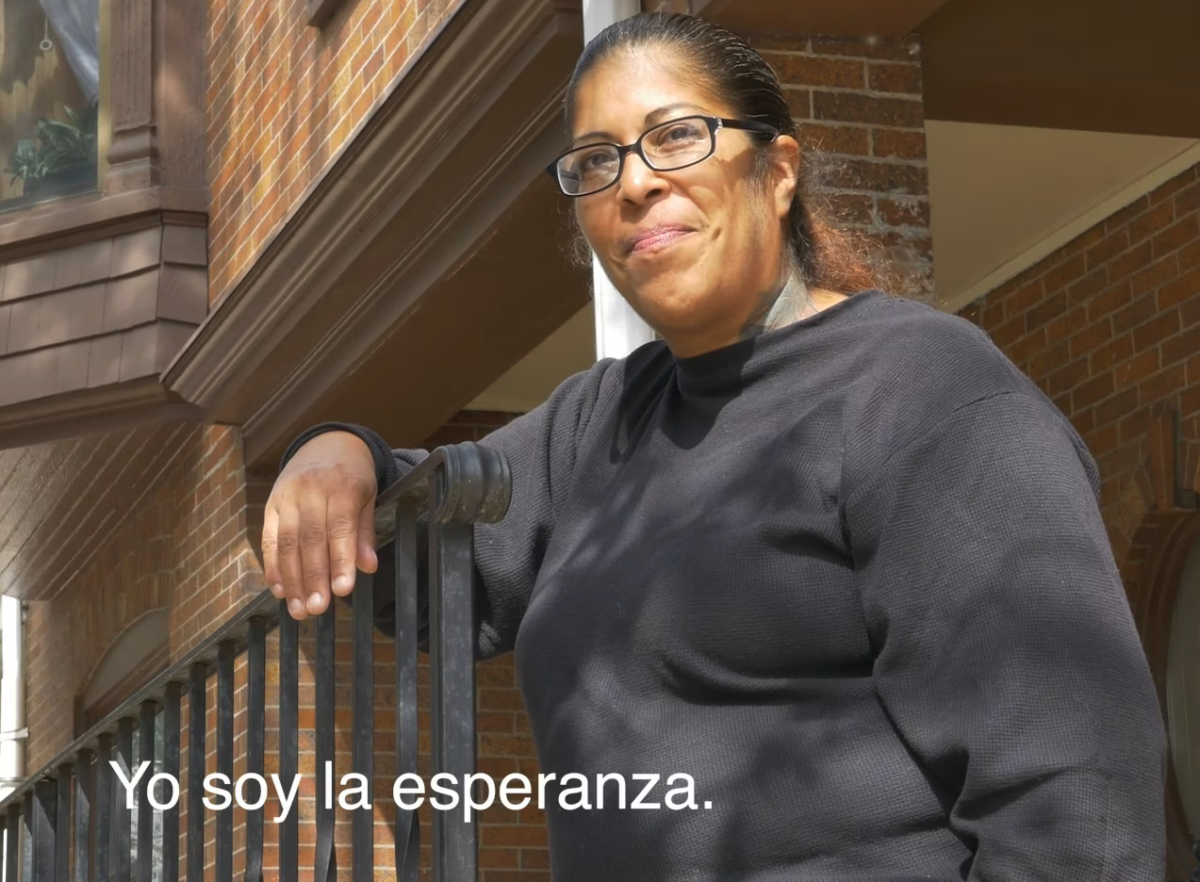

For their final projects, students worked in teams of four to pursue stories of relevance to ACED’s efforts. Story possibilities were gathered by Drew, who surveyed community leaders for ideas. Four stories were produced: a profile of an intentional, mixed-income housing community; a profile of ACED itself; a profile of young bikers who enact their freedom and vision for the city through city-wide rides; and a profile of a community activist who aims to protect the social fabric of neighborhoods she has known nearly all her life. Students were guided throughout every step of their process. They did preliminary interviews without cameras in order to gather information and start forming relationships of trust with people who would be featured in their documentaries. They wrote reflections after each conversation or shoot and the course instructors would comment on their reflections and questions. Students also practiced being accountable to each other in that they were responsible for evaluating team members’ participation and contributions.

Due to a grant from the Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium (LVEHC), we were able to support a public forum at the end of the fall 2018 semester to include a screening of student works. The December 13th event included a viewing of the four student films, spoken word poetry, step performances, and community testimonials and political action. After each performance or screening, an ACED organizer would introduce an issue or effort, point the audience to a place in the room where they could take an action—sign a petition, register their personal perspective, send a postcard to City Council, etc. It was an evening that brought together a wide array of perspectives, leveraged those perspectives into action, and met ACED’s mission of complicating the stories told about development. City officials, members of the Allentown Police Department, organizers, educators, and Muhlenberg College faculty and staff attended the event, forging coalition and inviting new stakeholders into ACED’s mission to lift up community voices and push Allentown towards development efforts that are dialogical rather than destructive. The films produced through this collaboration will be available for viewing on the newly released LVEHC Digital Archive.