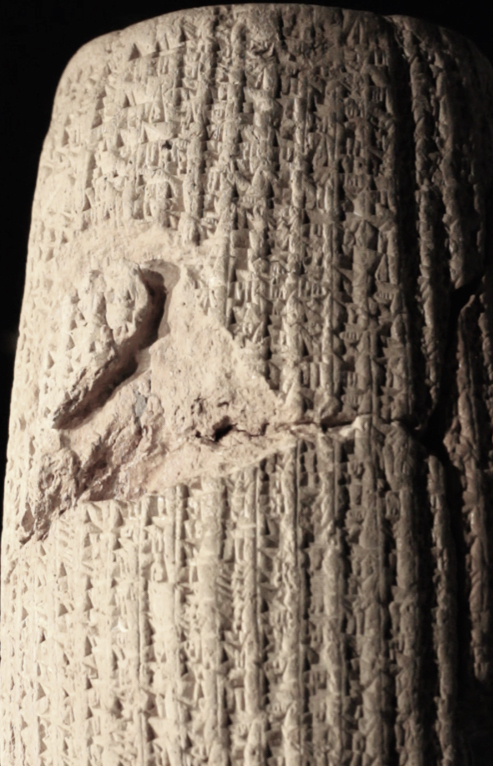

In 2013, London’s Iran Heritage Foundation (IHF), in partnership with the British Museum, launched the first-ever US tour of the Cylinder of Cyrus the Great. This cylinder is a clay tablet inscribed with cuneiform in which King Cyrus the Great in 539 BC celebrated his victory over Nabonidus to take control over Babylon. Inscribing a tablet with a victory statement was a common practice at the time, something like an inaugural address, but what set Cyrus’s tablet apart from rulers before him was that he promised a more benevolent rule in which people would be free to worship as they pleased.

Throughout the 20th century, the Cylinder has held a contested space in the Iranian self-narrative, located somewhere between the “first human rights charter” and a nationalistic relic. The executive director of IHF at that time, Haleh Anvari, had a bold idea to bring the Cylinder out of its venerable and academic museum context and to use the tour as a way of shining a light on the vast experiences and perspectives of the Iranian diaspora, as reflected in the Cylinder.

Haleh Anvari commissioned one filmmaker in each of the cities on the Cylinder’s tour to make a short film responding to the cylinder as artifact and loaded cultural symbol. I was chosen as the filmmaker for the San Francisco tour stop.

For my part, I wanted to explore the cylinder as serving dual purposes in developing certain national and/or pesronal mythologies.

While making this film, I was preoccupied by two images. One of which I discovered while browsing through the unique community library and public experiment, the Prelinger Library. The library is primarily a collection of 19th and 20th century historical ephemera, periodicals, maps, and books much of which is in the public domain. The library specializes in material that is not commonly found in other public libraries.

In the words of artist Taraneh Hemami: the archives represent an alternative to the official narrative. And here at Prelinger, I discovered a series of books published by Ketab Corporation which held a remarkable moment in history.

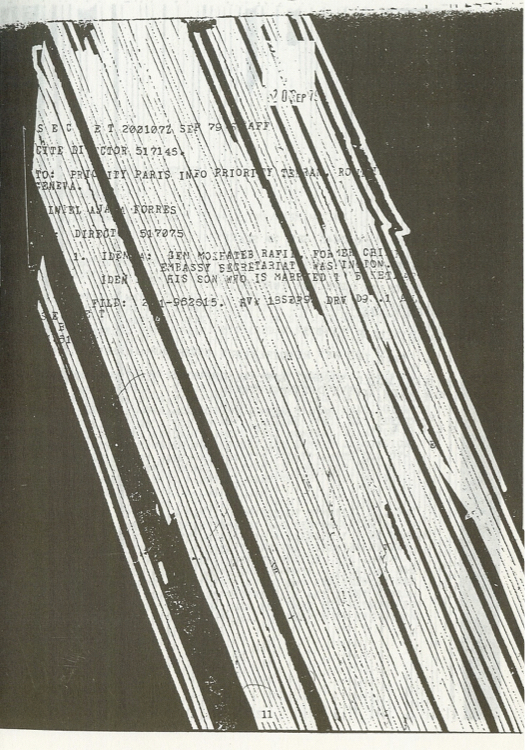

In 1979 at the height of revolution & one month before the king of Iran fell, activist students stormed the US embassy to expose US intervention in Iranian affairs. Those working in the embassy tried to protect the classified documents housed there by shredding everything.

You can see a scene of this recreated in the 2012 US produced film, ARGO, directed by Ben Affleck of all people.

These shredded documents, it is said, were then pieced back together by carpet weavers or young people and published for the world to understand how the US was interfering in Iranian affairs.

I was intrigued by this image and others like it of reassembled, re-constructed State Department documents. I was interested in the factual history here, the machinations of the US authorities to steer the revolution toward something amenable to US interests. But I was also intrigued by the image as visual metaphor, an invitation to read between the lines

And I saw here some visual symmetry between these paper shards stitched into cohesive sentences of political machinery, and the Cylinder itself. See the parallels below.

Two incomplete documents stitched into complete (or seemingly complete) narratives. You can see the symmetry really well if you flip the cylinder image vertically.

So this was my departure point. How do these two “artifacts” speak to one another? What resonances are there between these two moments: the moment in which the students of 1979 discovered themselves and their country through the probing eyes of the US state, and this current moment in which our community is being asked to see ourselves through the Cylinder, held up as a symbol of the best in Iranian values. What are the various narratives that impose themselves on the Iranian nation-state, by what political or sociopolitical interests are these narratives motivated, and how do they ultimately shape how we see ourselves as political subjects? These are the questions behind the film that I contributed to 7Sides.

The 7Sides film is more than a collection. It is one film spoken through 7 different voices. It’s a film whose language is best understood as a whole. The collection in whole is thought-provoking, sometimes elegiac, sometimes scathingly critical and always necessary conversation led by leading scholar-artists in the Iranian American community.